For decades, the global economy appeared to defy gravity. Even as central banks engaged in extraordinary monetary experiments, near-zero and even negative interest rates, trillions in quantitative easing, and ballooning fiscal deficits, inflation remained subdued. Although maybe indistinguishable, the reason was not magic, but sufficiently advanced technology. Moore’s Law, combined with the deflationary impact of digitization and global supply chains, offset the inflationary impact of monetary debasement. But this balance, which created a once-perfect time in economic history, may now be ending.

This article presents three models of the tug-of-war between technology and money creation. Each graph highlights a different scenario for the future, including our prediction of a $20 trillion tsunami of QE in 2026 and together they tell a story of how the deflationary power of technology once held back inflation, and why that may no longer hold true.

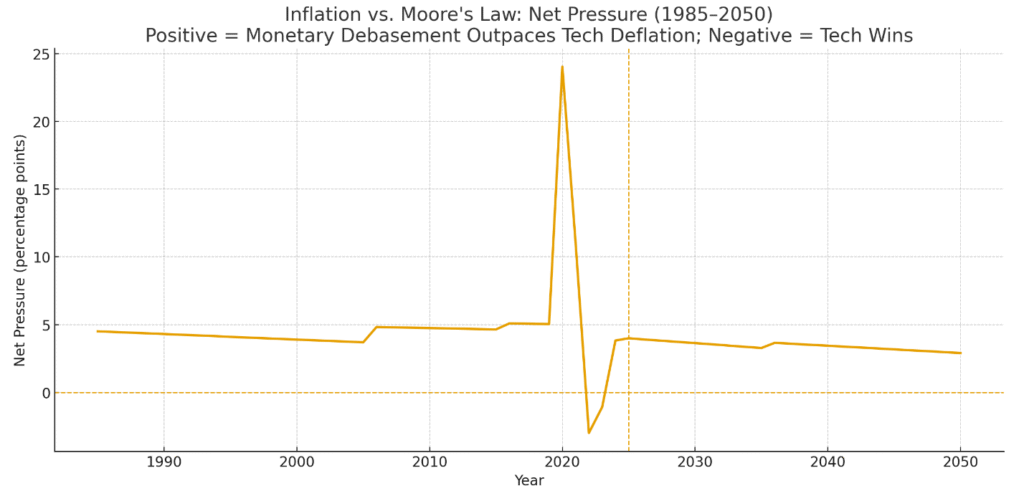

The Baseline Model

1985–2050: A stylized tug-of-war

In the baseline model, we assume steady fiat debasement (5% per year on average outside crisis periods) and a gradual slowing of Moore’s Law-driven cost declines. Technology’s share of the economy grows from ~5% in 1985 to ~35% by 2050. The result: while monetary debasement dominates in most years, technology provides a persistent counterforce, keeping net inflationary pressure modest.

Figure 1: Baseline model showing net inflationary pressure (positive values = monetary debasement dominates): FRED M2SL/M2REAL (2020–2023 spike & contraction); BEA Digital Economy (≈10% of U.S. GDP in 2022); Federal Reserve FEDS Notes on slowing ICT price declines; Intel on Moore’s Law; McKinsey (GenAI productivity potential). Assumptions: Pre-2020 M2 ≈6%/yr; 2020=25%, 2021=12%, 2022=–2%, 2023=0%, 2024+=5%. Tech price-decline rates: 30% (≤2005), 15% (2006–2015), 10% (2016–2024), 8% (2025–2035), 6% (2036–2050). Tech share grows from 5% (1985) → 10% (2022) → 35% (2050).

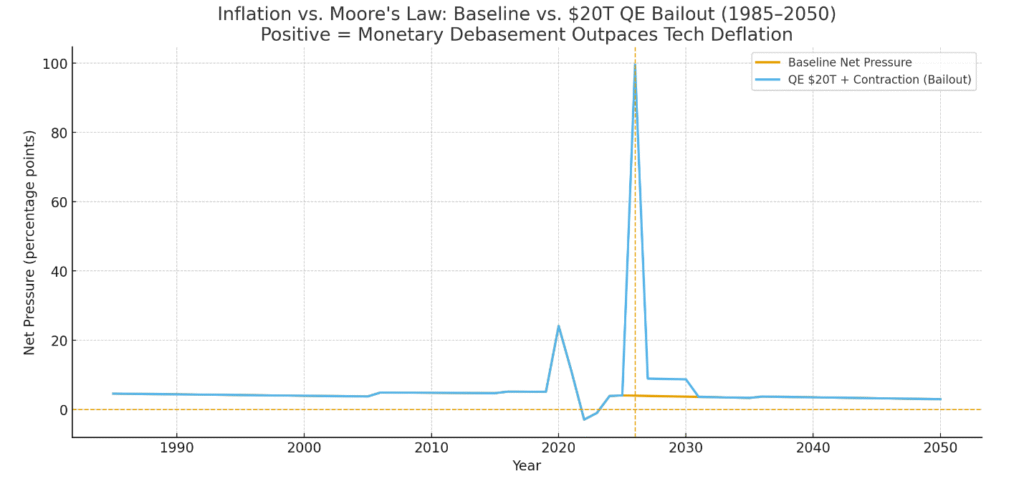

The $20 Trillion QE Bailout Scenario

2026 contraction + monetary rescue

Here we imagine a severe contraction in 2026, met with a massive $20 trillion QE bailout. The shock is modeled as a one-year 100% increase in money supply, followed by several years of elevated (10%) growth. Technology’s deflationary effects also weaken temporarily due to the recession. In this version, inflationary forces overwhelm technology in the late 2020s, but then monetary growth is assumed to stabilize back to 5%, allowing technology to regain some ground.

Figure 2: Bailout scenario showing a sharp spike in inflationary pressure after a $20T QE in 2026, with eventual reversion to baseline. Bailout scenario assumptions: $20T QE in 2026 -> modeled as +100% M2-like growth in 2026. 2027–2030 elevated money growth at 10%/yr. 2026 GDP contraction assumed to reduce tech share by 10% and tech improvement rates by 50% for that year only. All other baseline assumptions unchanged (pre-2020 M2 = 6%/yr; 2020=25%, 2021=12%, 2022=-2%, 2023=0%, 2024+=5%; tech price-decline rates as in baseline).

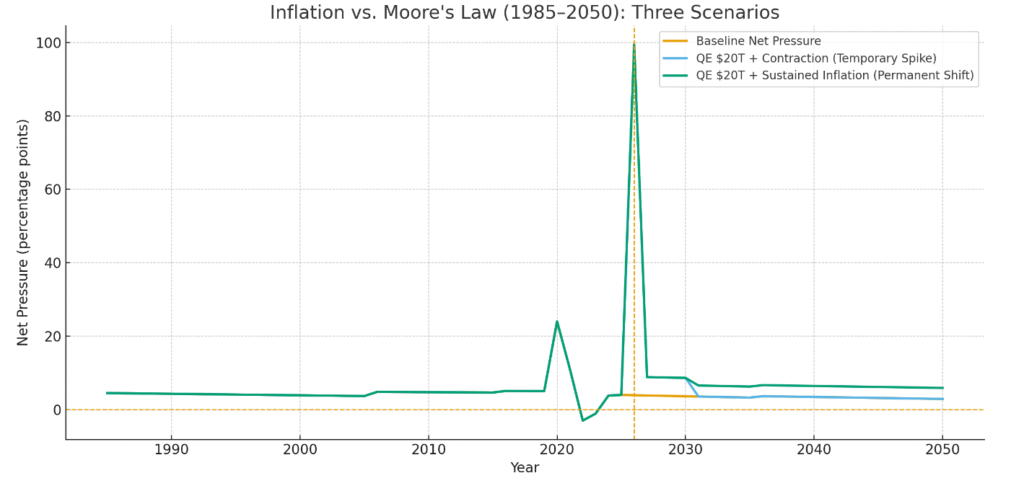

Sustained Inflation After QE

The permanent shift

The third scenario asks: what if inflation doesn’t revert? If $20 trillion QE of 2026 permanently raises the baseline pace of money growth to ~8% per year, the balance is broken. Technology continues to diffuse, but its deflationary impact is simply outpaced by sustained monetary debasement. In this world, inflation becomes the structural condition of the economy.

Figure 3: Sustained inflation scenario showing how technology cannot catch up once fiat debasement resets to a permanently higher path. Three-scenario comparison: (1) Baseline (return to 5% money growth aftershocks); (2) QE 20T Bailout in 2026, then reverts to baseline; (3) QE 20T with permanent shift to 8% fiat debasement from 2031 onward. Deflationary tech assumptions unchanged except 2026 contraction.

Why Inflation Stayed Low for So Long

From 1985 through the 2010s, advanced economies experienced a remarkable paradox: massive monetary stimulus without runaway inflation. Several factors explain this:

• Moore’s Law and ICT Deflation – The doubling of computing power every ~2 years drove down costs of digital goods by 20–30% annually in earlier decades. This spilled over into productivity gains in logistics, communications, and services, muting consumer price pressures.

• Globalization – China’s entry into the WTO and global supply chain integration exported deflation to the developed world. Wages, manufacturing, and materials were sourced at far lower cost.

• Financial Repression – Much QE liquidity was trapped in bank reserves, not the real economy. This dampened the pass-through to consumer prices.

• Demographics – Aging populations in Japan, Europe, and later the U.S. reduced aggregate demand growth, offsetting monetary expansion.

• Credibility of Central Banks – Even as they printed money, central banks retained credibility. Inflation expectations remained anchored.

This combination, relentless technological deflation, global wage arbitrage, and central bank trust, allowed even the loosest monetary regimes (negative rates in Europe, trillions in QE in the U.S. and Japan) to coexist with low inflation.

Why That Era Has Ended

Today, each of those forces is weakening:

• Moore’s Law is slowing as semiconductor scaling faces physical limits.

• Globalization is reversing, with reshoring, tariffs, and geopolitical fragmentation raising costs.

• QE has become fiscal dominance, with central banks financing government deficits directly.

• Demographics are shifting from deflationary (aging/retirement) to inflationary (shrinking labor supply).

• Credibility is under strain after the 2020–2022 inflation spike.

We assert that once-perfect time where technology prevented inflation has ended. The future will be defined less by deflationary miracles of semiconductors and more by the structural debasement of money.

There was a golden era, from the mid-1980s through the 2010s, where Moore’s Law, globalization, and demographics suppressed inflation so effectively that central banks could expand balance sheets without consequence. But with technology’s deflationary power fading and monetary debasement accelerating, that balance is gone.

If the first scenario holds, we may once again return to the technological deflation we once took for granted. But if we are correct and QE is on the horizon, inflation may spike temporarily or shift permanently higher. In either case, the tug-of-war between money and technology is no longer evenly matched. The age of effortless disinflation is over.